Polish politics, plunged into a pandemic spasm, has recently served us more than enough absurdities. But the fact that the first anniversary of last year’s All-Poland Women’s Strike gathered only about 800-1200 people in Warsaw is a different league. A fact that requires us to think longer.

Somewhere between another debate on Polexit, galloping inflation that is currently oscillating somewhere around 6.8 percent, horrifying reports from the Polish-Belarusian border and the daily circus of the Polish parliament in which, thanks to a member of the Confederation, we watched vodka being drunk, on October 19 the All-Poland Women’s Strike called a demonstration for October 22. This is the date on which Polish women began their struggle against the Constitutional Tribunal, which ruled on that day that a provision of a 1993 law permitting abortion when a foetus is predicted to have a „handicap or incurable disease” is unconstitutional.

The Constitutional Court held, in an 11-2 decision, that this provision violated the constitutional protection of human dignity. In practice, the decision meant that most of the 1,000 to 2,000 abortions legally performed in Poland each year became illegal. The ruling did not apply to the other two cases: abortion as a result of a crime (rape or incest) and a situation in which a woman’s life or health is at risk. In 2019, according to the Polish Ministry of Health, 1074 out of 1100 official abortions were cases of fetal abnormalities. Among them were cases of such horrific fetal deformities as Patau or Edwards syndrome.

Of course, the judgement was not made in a political and social vacuum. The CT ruling was merely the final result of a massive offensive launched by a coalition of anti-abortion movements, obviously supported by the Church and all sorts of far-right organizations. It collected 830,000 signatures under the Stop Abortion Act in 2016, forcing the Polish parliament and, as a result of the scale, also the whole society to discuss the 1993 law, the so-called „abortion compromise.” It was not s compromise at all. Abortion had been legal in Poland since 1956. Officially, in the case of difficult life conditions of a woman – but women had to submit statements about their life situation, but only until 1959 doctors were obliged to verify them. After that, procedures were performed on request, and what is now a remarkable irony, not only of Polish women.

Outbreak of social frustration

On the evening of October 22, young people spontaneously took to the streets of Warsaw. Stones were thrown at the police in Żoliborz. These events began a series of daily demonstrations throughout the country, which were attended by all those frustrated with the rule of Law and Justice, as well as the verdict of the Tribunal. On October 29, according to Police Chief Jaroslaw Szymczyk, about 430,000 people took part in 410 protests across the country. On October 30, more than 100 thousand of them took part in the largest mobilization, the so-called march on Warsaw.

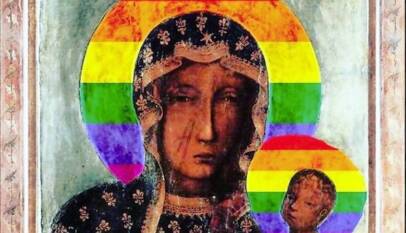

Thousands of demonstrators across Poland were fined under COVID-19 pandemic-related legislation, hundreds were arrested, and some were beaten by fascist thugs whom Jaroslaw Kaczynski called in a television broadcast to „defend the Christian pillars of European culture.” A completely new phenomenon was the significant politicization of smaller towns and villages across Poland, and the very clear anticlerical nature of the protests. There were instances of protesting women disrupting masses as they felt the Church was encroaching on their private lives. This was something new and shocking, including to the elites of the Polish Church, who live in their own completely secluded bubbles.

It ended on the evening of January 27, 2021, when the verdict of the Constitutional Tribunal was formally published in the Polish Official Journal. Several thousand people gathered in the streets of Warsaw.

From that moment it was only a matter of time before a tragedy such as the one that befell Izabela from Pszczyna. And not only her. According to the Abortion Dream Team:

„Based on #abortionwithoutborders calculations, as of April 2021, an average of 90 people a day are terminating pregnancies with pills in the country. Another 3 people a day go abroad for second trimester abortions to England, Netherlands. A large group of people go to Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Austria.”

What went wrong?

So why did the anniversary of the start of last year’s mobilization of the National Women’s Strike turn out to be a tragicomedy? Why were the organizers afraid to call for a demonstration beforehand because they thought no one would be there?

It seems that OSK was not at all prepared for social mobilization, nor for the protracted conflict with the authorities. All there was was loud slogans and bullish rhetoric. There was no strategy or even tactics.

After the first two weeks everyone could sense that the OSK leadership had no plans for the next days and weeks of struggle. The only way out was, in the eyes of the leadership, to radicalize the protest, that is, to blockade the streets of Warsaw, and perhaps other major cities. This formula was doomed to failure because it placed all hopes in the fact that the government would back down and not publish the CT ruling.

The huge popularization of the strike also seemed to be a problem for the leaders. No one foresaw such a great mobilization of people throughout Poland. But this could have been dealt with in the coming weeks of struggle. But almost nothing was done: some people did not know what to do, how to organize in the long run, nothing was provided for them, no training, no leaflets, no brochures. The only information that spread quickly was the number for Abortion Without Borders, which painted on walls and sidewalks all over Poland became a symbol of the struggle, just like the lightning, and the dates of upcoming demonstrations and rallies. However, without proper organization in the long run, this too was doomed to failure.

It was enough for the government to decide to wait out the protests and stay consistent. And they did both.

It was extremely frustrating to see that the political parties just watched what would happens next. Most of them supported the „abortion compromise.” Only the Polish centre-left, the SLD and the Spring Party, and the social democratic Party Together supported the right to free choice. It also seemed that among the protesters, some wanted the full right to decide about their bodies, and some were there only to protest against PiS and the Constitutional Court. The Nationwide Women’s Strike did nothing to change that. Where there is time for demonstration, there is also time for education and organization. In this case, the latter part was not in the plan from the beginning.

To move forward, we need accountability

On November 1, the leaders of the strike, among them Marta Lempart and Klementyna Suchanow, decided to set up a Consultative Council whose purpose was to create some kind of program for the movement. The founding members were people whose addresses are exclusively in the Polish capital. Some of them were people from liberal organizations satellite to Civic Platform, like the Committee for Defense of Democracy, but one person was also a former minister in Donald Tusk’s government. The rest of the committee were mainly friends and acquaintances of the leadership. They had no democratic mandate. The protest has since gone downhill more and more spectacularly.

Instead of recruiting people and creating active branches of the organization that would allow it to survive months of more and more demonstrations, would also provide ideas for new kinds of political struggle against the government, as well as provide a kind of institutional check on the police violence experienced by the demonstrators, the leadership decided to create an ephemeral body that is still unknown to the wider public. Moreover, the composition of the council indicated the choice of a coarse anti-signature path, which, as Polish politics shows, usually leads nowhere. This structure, based on successive people elevated by the Warsaw elite and media, had to collapse.

The problem of Polish politics, especially grassroots movements, is the lack of trust in politicians and activists, and even in political journalists. The moment of such a huge mobilization of women and men, especially young men, could be a moment of reckoning for Polish political culture, and this reckoning was demanded by thousands of people who were at the protests.

There is no institution in Poland around which a sense of Polish community has been built, except for the Polish Church. Polish state institutions or trade unions, due to the chaotic and disastrous in many spheres neoliberal transformation, are not deeply rooted in the Polish imagination.

This social void is filled not only by the Church, but also by a network of organizations subsidized by the government, general-military structures such as the Territorial Defense Forces, as well as media clubs, which were created many years before the right wing came to power. This was certainly the first attempt to create something on the scale of a mass civil society in Poland, obviously marked by an overtly right-wing-nationalist stigma. This initiative has no serious competition, and it should have.

Within months of publishing the ruling in the journal, the leadership of the All-Poland Women’s Strike decided to take part in real politics in its own way, once publicly blackmailing politicians of center-left and left-wing parties because of their support for the post-pandemic funds project presented by the government of Law and Justice and its satellites.

This event, along with the dissolution of part of the so-called committee – in an atmosphere of left-liberal call-out culture – created an atmosphere of farce around the organization. It did not help that there were constant reports about attempts to create a party within OSK, which were not demented by the leaders of the movement themselves. Moreover, in April of this year, feminists were cancelled by their allies who had the audacity to criticize the organization’s previous activities on OSK’s social media channels. In the end, no one knew what the entire movement was really about.

These problems and mistakes, combined with the pro-government narratives of the state media, and the perceived fatigue of the people, led to the normalization of the current state of affairs. It seems that next time people will go out not with the women’s strike, but rather the strike will go with them.

The recent demonstrations after Izabela’s death in the hospital in Pszczyna are proof of this. They were more like mourning marches, manifestations of remembrance, rather than another skirmish or battle in the fight for women’s rights in Poland. Without organization, the mobilization in the streets alone would be just a demonstration, not part of a larger struggle.

The way out

It is worth mentioning here the history of struggles for women’s rights in other countries. In Ireland those were referendums, accompanied by social mobilizations led by political organizations, both parties and activist organizations, that granted full rights to all citizens. It all started back in the 1990s, ending with the 2018 referendum abolishing the anti-abortion constitutional amendment. Such referendums have seen countries like Switzerland, Liechtenstein, San Marino, Italy, and many others in the 20th century.

It is possible that taking the referendum road now is an idea that could reinvigorate the movement, re-consolidate it, and get it back on track for open and vigorous conflict with the United Right government, and its allies from the ranks of the Confederacy.

It is within this path that feminist activists, women together with the celebrities, politicians and allies supporting them, could go out to the society and this is what these circles need most today. Such an approach would refresh politics in Poland, thus doing something that the Women’s Strike failed to do a year ago. And Polish politics needs refreshing in the fight for human rights the most.

Such an opening would create another – this time perhaps successful after the stories of KOD, OSK, or unsuccessful trade union mobilizations – opportunity to enter the political arena with a counterproposal to create a civil society in Poland, a proposal uncontaminated by the nationalist narrative.

And we need a new formula like fish need water, as anyone who observes the dynamics of the last year can see. As reported by Onet, it is even agreed with such an approach by OSK and people who care about Polish women’s rights.

Without this we will face more mourning marches, and hundreds, if not thousands of personal tragedies of women, their families and partners, which will lead us to even greater normalization of this anti-human situation. Everyone knows that this situation must change, even Tomasz Terlikowski, who recently spoke about it directly in the pages of Kultura Liberalna. However, on the Polish political market there is no strategy to win the right to abortion, the right to decide about one’s own body. Neither the parliamentary centre-left, which only attacks the idea of a referendum and takes pictures of itself in moments of crisis, nor the circles of the Civic Platform, which in reality are rather far from the idea of legalising abortion, have it. Only from time to time some politicians situated closer to the center mention, as Szymon Hołownia did recently, the idea of the referendum.

Let us not allow the rebellious, courageous involvement of thousands of people throughout Poland, which spread during these weeks of insurrection, in places where no one dreamed of any demonstrations, to be in vain. It may yet be the moment to create a truly democratic movement, broader and more transparent than anything on the corrupt, in the eyes of Polish citizens, political market. As the title of Klementyna Suchanow’s book proclaims, fighting for women’s rights is war, so if that is indeed the case, let’s finally create our own divisions.

How is the war in Ukraine changing Poland?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is changing the whole world. Its consequences are felt by …